My life cracked after my dad died. I didn’t want to die, but I wasn’t sure I wanted to go on living either, or rather how to go on living. Those were days in extremis. The only writer I could read, who felt trustworthy, was Joan Didion. Her words on dying and surviving and grief were drops of Gorilla Glue in the crack.

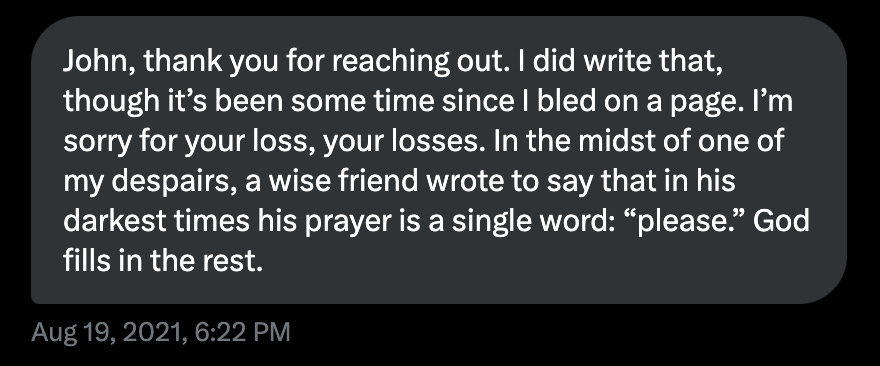

But there was another writer who wrote something then that was equally lifesaving. It happened via a Twitter exchange, back when I was still on Twitter and back when it was still called Twitter. Somehow I stumbled upon this article that rang true, felt trustworthy, Didionesque. It carried the byline “Anonymous.” I gave it a nod on Twitter and a friend told me, “That’s Tony Woodlief.” Thank God for friends. I reached out to thank him, and he responded with this:

There were many days then, still are in fact, that my prayer is a single word: “Please.” That’s it, not even an “amen” to boot. Just “please.” The hope that follows is that God fills in the rest, sorta like Gorilla Glue I guess. I have Tony Woodlief to thank for that.

Here’s a quick bio. Tony Woodlief is a writer who lives in central North Carolina. His work equipping state and local leaders to embrace democratic self-governance has led him to write a fair bit about politics in publications like the Washington Post and Wall Street Journal, as well as his 2021 book, I, Citizen, which inspired the award-winning documentary, Undivide Us.

He would rather everyone got along so that he could devote himself full-time to gardening and writing fiction. His short stories have appeared in Image, Dappled Things, Reckon Review, and elsewhere. His novel, We Shall Not All Sleep, was published by Slant Books last fall. While his struggles with faith, parenting, and loss are often close to the surface in much of what he writes, he's delved directly into them for years in various essays and blog posts, the most recent of which can be found on his relatively new Substack, "Fragments Against Ruin."

What are you reading right now, and how is it challenging or confronting you?

I’ve started thinking of Philip and Elizabeth as my wrecking crew. They’ve never met but they’re passing a hammer back and forth between them to take studied whacks at the machinery of my heart.

Philip Rieff was a sociologist who served in the U.S. military during WWII, lost family in Auschwitz, rose to academic prominence with his transformative study of Freud, married a 17 year-old Susan Sontag when he was her professor, won all manner of scholarly accolades, then embraced a monastic seclusion for the next thirty years. He only re-emerged in the final months of life to drop an abstruse banger titled My Life among the Deathworks.

I won’t summarize it other than to tell you that at his core, Philip believed Hitler won. That barbarism masquerading as enlightenment was birthed into the world and Hitler was its logical culmination. That more Hitlers will come and even now are among us, each nearly to a man imagining he is the antithesis of Hitler.

What this means is that nothing I do other than loving my babies and singing in my church choir can hold back the darkness, and most of the rest of what I do probably makes things worse. I already suspected as much. That darkness is coming and all any of us can do is try to face it holding the hands of those he loves. I think this is why I’ve mostly stopped writing, or even saying, really, anything of deep interest. Because who am I, and what does it matter anyway? We’re already drowning in a sea of inapt words.

Before I knew Philip’s story I could feel the loneliness in his work. He’s telling us how we’re going to go out, as a civilization, and he knows there’s not a goddamn thing anyone can do about it, but he stuffed his pages into a bottle and hurled it into the word sea nonetheless. There’s a nobility in that, I think. In writing out the truth with no expectations.

Okay, I lied earlier. I am writing. I write for the drawer, as Solzhenitsyn once said. I grieved my obscurity for a time, but afterward came freedom. There’s no cancelation if you write to yourself. No readers to disappoint. You can cut down to the bone, to the meat within the bone. Now, to have Philip rocking the foundations of what I thought I thought about culture and faith and the future of humanity, and learning he labored in solitude until his dying days, well, I feel a kinship.

I should try to be a songwriter. Elizabeth Grant is shockingly direct one stanza, obscure the next. Come to think of it, so is Philip Rieff. Like they want you to lean in close so they can slap you. What an item they would have made. And he would have called her Elizabeth no matter how many millions call her Lana.

What does a grim scholar of sacredness have in common with a mezzo-soprano (or perhaps contralto; there’s some debate about this) femme fatale? Just consider “Did you know that there’s a tunnel under Ocean Blvd?” from her 2023 album of the same name, which all we who are not Swifties know damn-well deserved the Grammy.

The tunnel she’s singing about had mosaic tiles and was a lovely discovery to be had but it was bottled up in 1967 and those colorful tiles have no light now to make them sing and are dropping one by one onto the cracked concrete. Philip likewise understands that the fragments all around us are not the thing but the vestiges, the proof of a thing that was and still is above us, a sacred order to which we were once oriented, and whose spurning yields fragmentation and doom. His blow at the deathworks was to call us to see what has been covered over, and to remember. “Don’t forget me,” Elizabeth/Lana implores over and over in that song. “Don’t forget me.” But the tunnel’s beauty lies in ruins as will hers, and it is forgotten as she will be forgotten, and she relishes the sweet tragic inevitability.

Elizabeth and Philip are not the only writers to regret a declining facility in our culture to sense a world beyond this visible world, but she epitomizes Philip’s admonition that “the first object to be read in sacred order is oneself.” In this album she is abandoned beauty and coquette and whore, she is the perennial side piece, she is the girl whispering on the back church pew. “When’s it gonna be my turn?” she asks, knowing the answer, begging her lover to open her up, to fuck her to death, to love her enough for her to love herself. How often in her songwriting has she asked to be wrecked, fucked, shattered? Who among us doesn’t want to be broken open? Who doesn’t tremble at the thought?

Philip and Elizabeth have a lot in common, I think. That’s why their hands fit so well on that hammer. “I heal with the thing with which I wound,” quotes Philip from Exodus Rabbah. Amen.

Tell us when you were last amazed, astonished, or awed. Charm us with the whole sucking story.

My godfather’s name is George. The dragonslayer. He’s in his late 80’s, so you might not know it to look at him but George is a badass. He wouldn’t like being called that, having spent so many years in prayer and repentance. George is farm strong. George was a military chaplain in Vietnam during the Tet Offensive. George has seen some shit. He had a sweet little Elizabeth of his own, but she passed a few years back. George has blessed our table many an evening, and it’s one of those recent evenings I want to tell you about.

My property is a haven for copperheads. The reason so many people get snakebit in North Carolina is because of the copperhead. It’s hard-wired not to move when you approach. It just lies there and strikes. A few years back I went at a nest of them with my shotgun, forgetting I had double-aught buckshot in the tube. The slaughter—and landscape damage—was excessive. I guess I thought I’d broken the spirit of my local copperhead contingency. George was in Nam, and if he had caught me thinking such a thing he would have cautioned me that native inhabitants stick harder than interlopers might think.

The same goes for serpents, and the Serpent. George has a way of gently correcting my soul when it strays. Of warning me that the coming Judgement spares no man. Never presume on the neglect of the serpent, he might say.

On this particular evening, George prayed over our meal and gave us his time and took his leave at a decent hour as always, and on his way out the door he cautioned me to be safe in my upcoming journey. Because the next day was garbage day and I had an early flight, I walked the trash bins down our long tree-shadowed drive to the street. On the way back up the drive, because my hands were now free, I used my flashlight. Then I came upon it, inches from where I had just passed: a copperhead, its head freshly obliterated by George’s wheel.

The path is perilous. Thank God for dragonslayers.

~

Thank you, Tony. Really, thanks.

Nothing makes me happier today than the partnership of this piece, John and Tony, two of my favorite living writers, two of my favorite living men.

Loved reading this! Thank you!